No one should condescend to Agatha Christie – she’s a genius

Christie is consistently dismissed as merely a brilliant plotter of mysteries. But she’s so much more than that.

“Agreeing to marry you made me feel so powerful … The other suitors thought me simply wonderful, and, of course, it would have been very nice for them to have me. But I’m everything you most dislike and disapprove of, and yet you couldn’t withstand me! My vanity couldn’t hold out against that. It’s so much nicer to be a secret and delightful sin to anybody than to be a feather in his cap. I make you frightfully uncomfortable and stir you up the wrong way the whole time, and yet you adore me madly.”

That’s the vicar’s wife speaking, at the beginning of The Murder at the Vicarage by Agatha Christie, a writer too often dismissed as merely a brilliant plotter of mysteries. As I hope the above quote proves, it is a charge that’s grossly unfair. Christie’s books are so much more than great puzzles. Each of her novels demonstrates a profound understanding of people – how they think, feel and behave – all delivered in her crisp, elegant, addictively readable style. While immersed in a Christie mystery, you might not notice the wisdom sprinkled throughout the pages because you’re having too much fun, growling with frustration because you’d love to be able to guess the solution but can’t.

So why are so many determined to underrate Christie? Raymond Chandler sneered that a Hercule Poirot mystery was “guaranteed to knock the keenest mind for a loop. Only a half-wit could guess it.” He dismissed the British golden age detective novel as “futzing around with timetables and bits of charred paper and who trampled the jolly old flowering arbutus under the library window”. Chandler described the crime cases in his own novels as “a perfunctory mystery element dropped in like the olive in a martini”. Surely anyone who doesn’t care about puzzles or mysteries should write in a different genre: letters of apology to greater writers than oneself that one has unfairly maligned, perhaps.

What Chandler failed to understand about Christie’s artistic project was that all these seemingly trivial details – the charred paper, the timetables, the plant on the windowsill – are vital. Christie knew detail mattered; she knew that those who ignore the apparently minor have little or no chance of understanding greater truths. That’s why solving the puzzle feels so urgent, and why plot always takes centre stage in a Christie novel – because how else are we truly to know who a person is until it has been revealed what he has done, and tried to hide, and why?

Without plot, there is no reliable access to character; Christie understood this. Her characters are properly, realistically three-dimensional – which doesn’t mean what many seem to think. Christie has been criticised for two-dimensional characterisation, but this, again, is inaccurate. The third dimension of a Christie character remains hidden for much of the novel, while that person presents himself superficially as he would like to be perceived: as a type, a glossy surface designed for public consumption and approval. Meanwhile, the third dimension – the maskless true self – emerges in the tiniest of glimpses. These hint at the real nature of the murderer, or of a person whose disposition renders them incapable of murder, and they are essential clues: if the reader spots them and interprets them correctly, she stands a chance of solving the mystery. And yes, these clues might involve a piece of charred paper. Who burned the paper, and why? When we no longer care about the answers to these small questions of human action and motivation, we’ve lost interest in people and in life, and should probably give up writing and reading novels altogether.

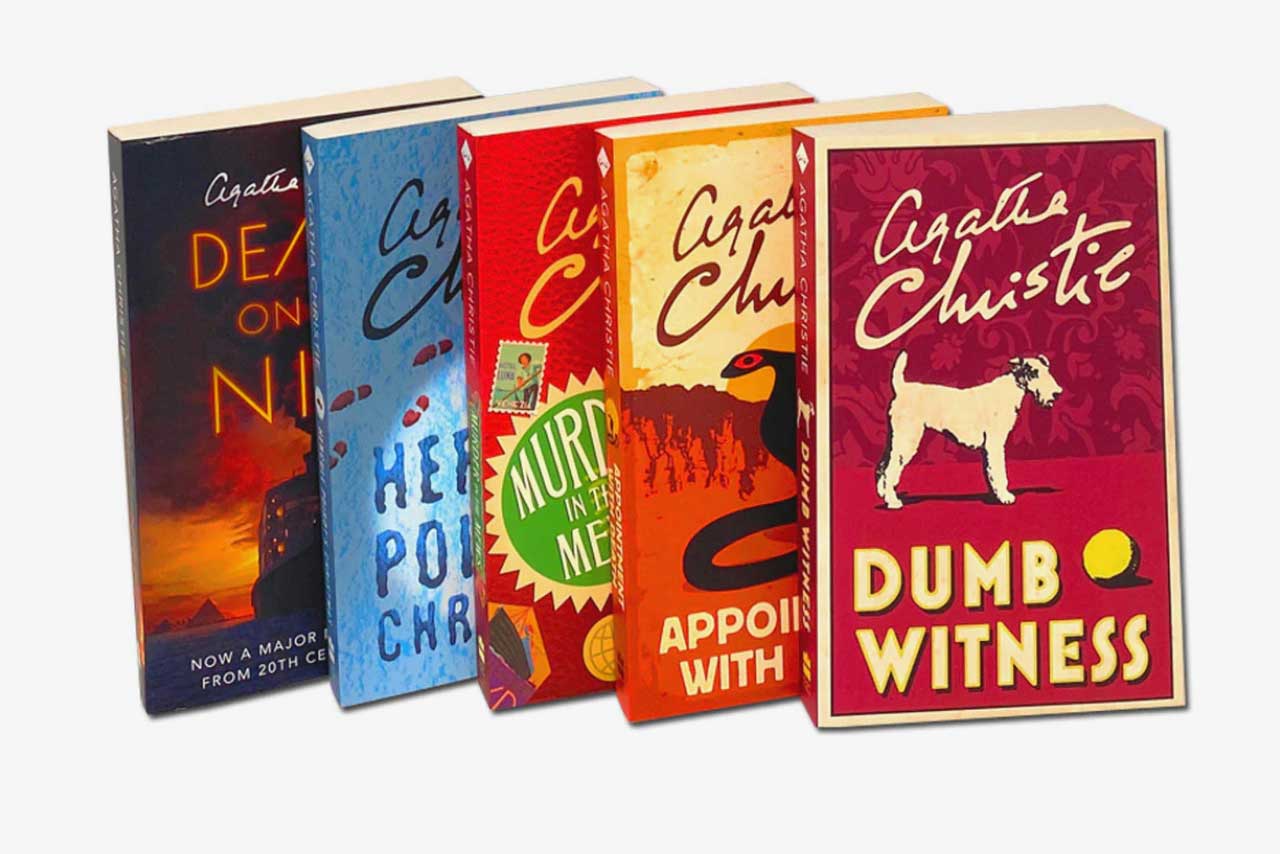

As a passionate Christie fan, I could explore her novels all day long, on every possible level, but there’s also a strong element of magic to her brilliance that defies analysis. How are her books able to be, simultaneously, simple enough that 12-year-olds can love them, yet complex enough to pose an impossible challenge to a bright adult mind? They’re light and jolly and fun to read, but also constantly aware of the dangerous lure of evil. In Death on the Nile, Poirot warns Jackie de Bellefort, “Do not open your heart to evil. Because – if you do – evil will come … It will enter in and make its home within you, and after a little while it will no longer be possible to drive it out.” It’s a good argument for aspiring to forgive Chandler, as well as a brilliant moment in one of Christie’s best novels.

In the process of preparing to write my own Poirot novel, I realised that Poirot himself is also a miraculous blend of opposites. He is the perfect memorable caricature, with his luxuriant moustaches, egg-shaped head and fussy ways – the hyperreal cartoon-like superhero who happens to pop up when needed to solve a crime – but he is also a real person with depth, and past pain, and a third dimension that will forever remain hidden, which makes us believe in its presence all the more.

Who else could create, or has ever created, a detective as necessary and enduring as Poirot? What if Christie is the best not only at plotting but also at everything else? She has sold billions: more books than any other novelist, ever. What if that’s because she is an unparalleled genius? As Poirot says in Murder on the Orient Express, “The impossible could not have happened, therefore the impossible must be possible in spite of appearances.”