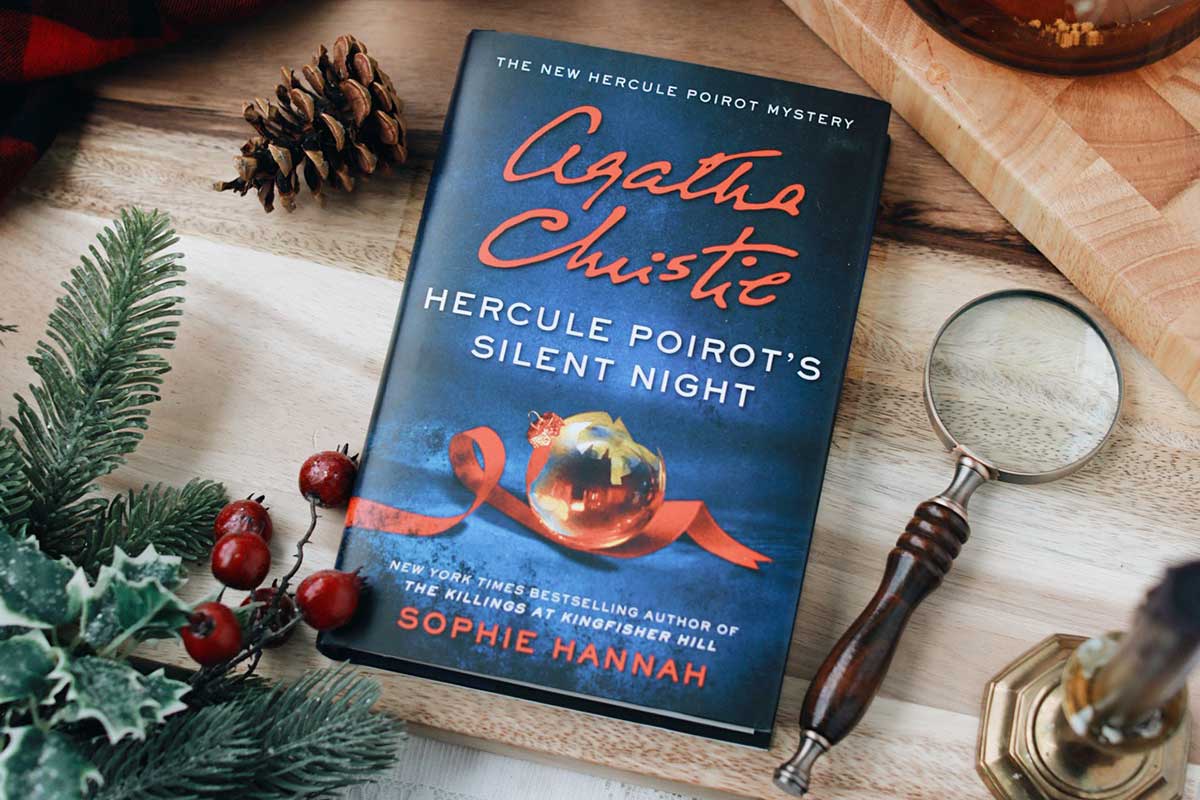

Sophie’s New Poirot Novel!

Available now in hardback, audio and ebook

How the book begins…

New Year’s Eve 1931

My experiment was not working. I laid down my pen and considered tearing the sheet of paper into strips. In the end, I crushed it into a jagged ball, aimed it at the fire that was blazing in the grate, and missed.

Hercule Poirot, sitting across the room from me, looked up from the book he was reading. ‘Your endeavour displeases you, mon ami?’

‘Dismal failure.’

‘Try placing an unmarked page in front of you. Immediately, your mind will produce better ideas.’ His green eyes darted to and fro between the neat pile of paper on the corner of his desk and the crumpled ball of my failed project, which stood out prominently against the backdrop of his otherwise pristine London drawing room.

I knew what he was thinking: on my way to get more paper, I would surely take the opportunity to rectify the disorder that was entirely of my creation. Hercule Poirot is not a man who can tolerate anything in his immediate vicinity being in the wrong place for more than…how long? If I did nothing, would it be seconds or minutes before he asked me to tidy up the mess I had made?

Determined not to tarnish my record as an exemplary guest, I moved quickly. My second attempt landed the offending object in the fire where it belonged. I returned to my armchair without availing myself of a clean sheet of paper. ‘You do not wish to try again?’ said Poirot. ‘You are giving up on your — what did you call it? — your “top hole” idea?’

‘Some ideas are appealing only until one tries to make them a reality,’ I said. My mistake had been to try to turn mine into after-dinner entertainment, when it was clear to me now that any species of fun was the very last thing it should be.

‘Perhaps you could tell me what you had in mind, if it is no longer to be the great surprise —’

‘It was nothing, really.’ I was too embarrassed to discuss it. ‘I shall prepare a crossword puzzle instead.’

‘Such secrecy.’ Shaking his head, Poirot leaned back in his chair. ‘Always, when I think about secrets, I shall remember the words of Miss Verity Hunt in her bright red evening gown. Do you recall them, Catchpool?’

‘Unfortunately, yes.’ I considered Miss Hunt’s supposedly sage advice to be quite the most ludicrous bilge I had ever heard.

Naturally, Poirot repeated the irritating axiom, perhaps in the hope of provoking me: ‘“Whatever you most wish to keep hidden, steel yourself for the ordeal ahead and then tell it to the whole world. At once, you will be free.” This is, I think, great wisdom.’

‘It’s codswallop,’ I said. ‘You will be free only from the secrecy — which you chose in the first place because you preferred it to all the things you won’t be free of for very long if you reveal all: endless interference and pestering from every quarter, no doubt. And that is if you are not breaking the law. In the case of a criminal — let us say, a murderer — you would hardly be free from the hangman, would you, if you announced that you were the guilty party?’

Poirot nodded. ‘I too am considering the case of a murderer.’

Neither of us spoke the name of the one who was still very much in our minds.

‘It is true,’ he said. ‘Once the crimes were committed, subterfuge became necessary in order to evade justice. But I wonder… Without the determination to keep the terrible secret at all costs there would have been no motive to commit any murders at all.’

‘Say that again, Poirot.’ I thought I must have misheard.

‘It is obvious: if the killer had not decided that it was worth committing two murders in order to keep the secret hidden—’

‘That is quite wrong,’ I interrupted, unable to contain my protest. His mistaken pronouncement was as intolerable to me as my paper ball on the floor had been to him. ‘The motive for the murders was not a fear of other people finding out. That wasn’t it at all.’

‘What fit of delusion is this? Of course that was the reason!’

‘No, it was not.’

Poirot looked alarmed. ‘I do not understand your meaning, mon ami. Do you not recall hearing with your own ears when the killer confirmed —’

‘As clearly as you do.’ It was little more than a week ago that Poirot had removed all need for further deception on the part of the murderer by revealing the full facts of the case himself, in his inimitable fashion. His deductions had been correct in every detail, and yet…how fascinating and frustrating that he was so wrong about the why of it all — and that his mistake should only now become apparent, eight days later.

I searched his face for signs that he was amusing himself by testing me, and found none; he meant every word of it. How extraordinary.

I fell silent for a while, assuming he must be right and I wrong. Traditionally, that was the way we did it. Could this be an unprecedented deviation from that general principle? The more I tossed the question around, the more certain I was: the Norfolk murders that Poirot had just solved so brilliantly were not committed in order to keep the killer’s secret. To believe this was to misunderstand, profoundly, what had taken place at St Walstan’s Hospital and at Frellingsloe House between 8 September and Christmas.

I hurried to Poirot’s desk and took four sheets from the top of the stack of clean paper. I have written, so far, an account of every case that Poirot has solved with my (infinitely flawed but always devoted) help. I had not yet started on my retelling of the Norfolk murders, however. Until this moment, it had felt too soon to do so.

There were still a few hours before dinner. I would not normally embark upon something so important at the very end of a departing year but I was unwilling to wait a second longer. Silently, I said to myself, ‘Let the wise reader be the judge of whether or not secrecy was the motive.’ Then I picked up my pen, and went all the way back to the beginning…